Welcome To A Safe Haven

Trump Isn’t the Only One Spewing Economic Nonsense

When I wrote Is Fine Wine Really an Inflation Hedge?, I received a few comments from people in the industry that went something like this:

“Nice analysis, but just not the kind of messaging we’d use to sell wine.”

This is exactly why In the Mood for Wine exists: a safe haven from the unsubstantiated claims that swirl around the wine industry—often just so that “they can sell more wine.”

I have no issue with disagreement. I welcome it. This is a free world, and different perspectives and interpretations of the big data are not only allowed—they’re essential.

I believe deeply in the Socratic method.

What I do take issue with is the disingenuous—and often ignorant—way wine is sold. It’s why the moment I mention “wine investment,” people start telling me stories of how they were scammed.

Mis-selling is the worst kind of selling.

The latest in a long line of misleading narratives is that wine is now “a safe haven asset,” especially post-Trump tariffs and in light of falling stock markets.

Why is lying about wine still the default marketing strategy?

Wine is wine is wine.

But first: what is a safe haven asset?

A safe haven is an investment that’s expected to hold or increase in value during market turbulence—ideally with negative or near-zero correlation to risk assets like equities. Safe havens are where investors turn to limit downside.

Some examples:

Cash (US$), which is often called the only true safe haven—though it offers no real return and loses value to inflation.

Gold, the star of the category: it can’t be printed, isn’t tied to government interest rate decisions, and has intrinsic scarcity as a physical commodity.

So why do some argue that wine belongs here?

The reasoning goes:

Wine is a physical asset like gold.

It has scarcity.

It’s said to be uncorrelated to financial markets.

Therefore... it must be a safe haven.

Except, that’s not how it works.

Why Is Wine A Poor Safe Haven Asset?

Using correlation matrices to suggest wine behaves differently from stocks is misleading. As Sébastien Page of T. Rowe Price put it in When Diversification Fails:

“One of the most vexing problems in investment management is that diversification seems to disappear when investors need it most.”

In other words: correlations spike when markets crash. And in the 2008–2011 period, wine’s correlation with equities increased—not decreased.

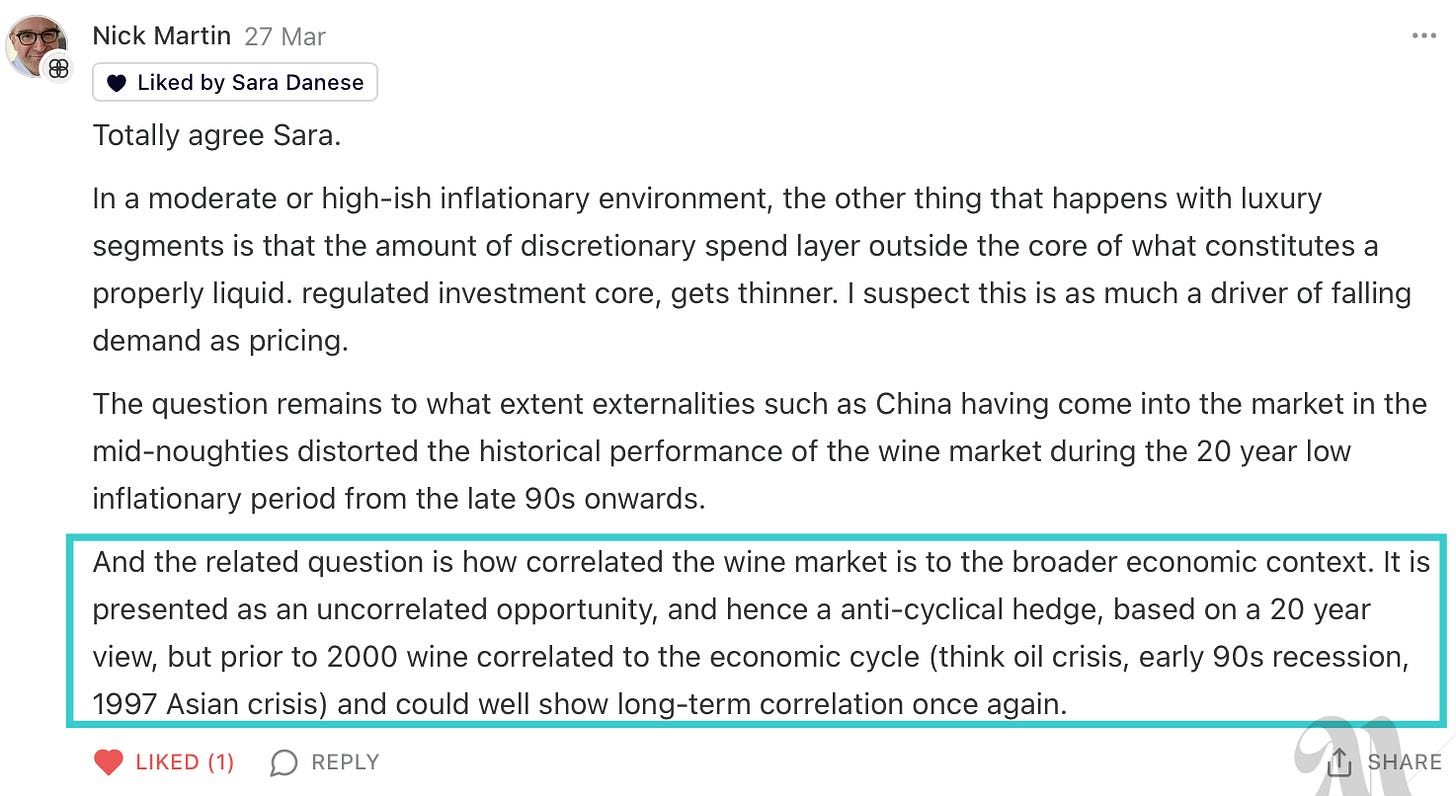

More importantly, we shouldn’t view correlation as a fixed point in time. What matters is how assets behave when it really counts—during drawdowns. And as Nick Martin, CEO of Wine Owners, noted in my last piece, we lack deep historical data pre-2000 to draw confident conclusions.

But if we look at wine for what it really is—there’s a clearer picture.

Wine is a cyclical assets in the world. Like other discretionary luxuries, it is tightly linked to market liquidity. It’s also illiquid—hard to sell, subject to regulation, and lacking price transparency.

That’s not what you want when markets are crashing.

Yes, people argue that “rich people will always buy wine.” But unless you’re planning to drink your portfolio to forget the world is on fire, that logic is a bit thin.

And this doesn’t even account for Trump’s tariffs.

Some in the industry suggested US investors warehouse wines in Europe and wait it out, hoping the tariffs would be reversed. But let’s be honest: most US buyers had already backed away well before "Liberation Day" (as can be seen in Liv-ex chart below).

As Matthew Star at WineBourse wrote:

“It is also likely many US buyers will choose to sell wines in Europe. When combining the costs of delivery plus this new 25% tax on EU wine, it could be more cost-efficient to dump wines—even if incurring heavy losses.”

And let’s not forget—wine, like real estate, is a transaction-based asset (i.e. an asset that doesn’t trade continuously on the market). Which means index data doesn’t accurately reflect its volatility. This phenomenon is known as volatility laundering, a concept explored by Dr Gertjan Verdickt in his paper Volatility Laundering: On the Feasibility of Wine Investment Funds.

So, why not just sell wine as it is?

Why pretend wine is a safe haven or an inflation hedge?

Wine isn’t a liquid asset. It’s not a hedge. It’s not safe in a downturn.

But it is:

An asset that improves with age.

A modest diversifier—when added in the right proportion.

A store of value in certain market conditions.

An aspirational luxury product.

And, in the worst-case scenario?

You can drink it with friends and forget the market’s burning.

Cheers,

Sara Danese

P.S.: Pieces like this won’t win me many friends in the industry 😂 But if you like your wine analysis raw and unfiltered, consider a paid subscription or share In the Mood for Wine and help grow our community! Thanks.

Wow Sara, so much to dive into here and a really interesting topic!

As you suggest there is no definitive answer; there is just not enough historical data to draw certainties from and even if there was, we would be talking about what has happened not what will happen.

To my mind, the rolling correlation charts here don’t give any reason to suggest wine is any more correlated with stocks than gold.

Completely agree that what matters is how assets behave during drawdowns and while wine fell in 08 (an unprecedented financial failure), it reached new highs by early 2010 and the S&P didn’t do so until 2013.

The wine bull run from 2020 to 2023 coincided with both stocks and gold falling in unison. Yes, it was followed by a wine crash and a stock market rally but that supports the argument for low correlation. (Again this is a short historical timeframe with few examples to draw from.)

Context is really important here too. While we might debate which is a better diversifier wine vs gold, wine appears a much better portfolio diversified than many other assets. The rolling correlation charts S&P 500 vs corporate bonds, Nikkei 225, Hang Seng etc. generally hover around or above +0.5. Even bitcoin and the S&P have had a rolling correlation above 0.5 since 2022.

Of course, some factors that affect stocks also affect wine, like how wealthy people are feeling or interest rates but there are also a tonne of factors that either only affect wine or affect wine in an idiosyncratic way:

- Crop yields impact on scarcity

- Long-term impacts of climate change

- Wine specific boom-and-bust trends like the 09-11 boom in Chinese wine interest, particularly in Bordeaux.

- Trends across the globe especially in emerging markets economies, a few studies have noted as emerging markets grow in wealth (think Brazil, India etc) fine wine tends to enter the zeitgeist.

- Veblen good dynamics, high price of some wines in effect drive demand. The likes of DRC just seem to go up and up in the long-run.

While I agree with a lot of what you have said, I feel like you’re leaving out some of the argument and evidence in favour of wine as a diversifier. I think we agree that the data doesn’t suffice alone and the theory plays an important role.

p.s. Sorry for the essay response!

Excellent post, as usual!