In the mood for wine is the only newsletter for the next-gen of fine wine collectors and investors. It’s free. The best way to keep it free is to share it with everyone.

Hello fine wine lovers,

For the last year, I’ve been playing with the Saturnalia Model Portfolio, built using the Saturnalia wine investment platform (you can read the background of this project here). If among my readers there are people on the fence about fine wine investing, I certainly did little to convince them that it’s a worthwhile effort. You lost money! I hear some saying… regardless, fine wine investing is a long-term effort. 2023 has notably been a challenging year for wine investors, marking it as the least profitable in the last decade.

The debate over the legitimacy of fine wine as an investment has intrigued many. Certainly, the whole point of this newsletter is to encourage fine wine as a legitimate investment asset class.

Some see problems:

Selling wine takes longer than selling stocks.

Wine needs the right storage, which costs money.

Wine merchants take 10-15% each way.

Some wines in the market are fake, which is a risk.

While you can easily value stocks, valuing wine depends on many things like its age and where it's from.

Investing all in one type of wine is risky.

…

However, fine wine offers a unique advantage — it's tangible. Because of this, it offers a different kind of value from stocks and bonds, in a sense, it holds a more subjective value than stocks and bonds because it also needs to account for one’s personal taste. Did you hear that, Australian stockbroker Danny Younis, for example, made the comments during an auction of his collection of 5,000 bottles of fine wine, calling his DRCs “effectively just glorified fermented grape juice.”

In the spirit of transparency, I'll assess the portfolio's performance, noting two things: that the record is relatively limited and many conclusions might not be meaningful; the second is that fine wine has a long way to go to catch up with other asset classes in terms of transparency and data availability.

Returns

Cumulative Returns (1 year, end of August 2023)

Portfolio: −4.40%

Benchmark (Liv-ex 100): −11.20%

The fulcrum of investing is creating value, starting with £100 and ending up with £110. Everything else is secondary. Even in challenging years. That’s why it’s important to assess the portfolio performance in absolute terms, first and foremost.

There is no denying that 2023 has been a down market for fine wine in general. In absolute terms, the underperformance of this portfolio was driven by Ausone, while Figeac pared back some of the losses with its incredible rise to 1er Grand Cru Classe (1erGCC) A. A more in-depth analysis is in the Holdings section.

Secondly, by comparing a portfolio's returns to a benchmark, investors can determine how well the portfolio performs relative to the market or a specific market segment. It helps distinguish between general market trends and the portfolio manager's skills. In relative terms, the portfolio surpassed the Liv-ex 100 by 6.8%. This can be attributed to the selection of safer fine wines.

Key Risk Metrics

In the spirit of the Barcolana sailing regatta that just past, this metaphor can help distinguish between the risk metrics used to distinguish between absolute and relative performance.

Imagine you're watching a boat race where all the boats are racing against the current of a river. The current represents the overall market or economic conditions.

Now, think of beta as how sensitive each boat is to the current. If a boat moves with the current just like most other boats, it has a beta of 1. If it's more sensitive to the current, speeding up more when the current gets faster and slowing down more when the current is weaker, it has a beta greater than 1. On the other hand, if a boat is less affected by the current and remains more stable, it has a beta less than 1.

On the side of alpha, it's like evaluating the skill of the boat's captain. If a boat's captain can navigate the boat better than expected given the strength of the current, finding shortcuts or using efficient techniques, then they have a positive alpha. If they perform just as expected based on the current, the alpha is zero. But if they don't do as well as they should be given the current, then they have a negative alpha.

So, in this analogy, beta helps you understand how a boat (or an investment) might react to the river's current (or market movements). In contrast, alpha gives you a sense of how skilled the boat's captain (or the investment manager) is at navigating against that current.

Beta: 0.431, meaning that the portfolio is less sensitive to the movements of the Liv-ex 100 benchmark, both when the movement is up or down.

Alpha: 0.73%, meaning that when the benchmark returns are zero, the portfolio is expected to have a return of 0.73%.

Volatility (Standard Deviation):

Provides a sense of the overall riskiness of a portfolio. It gives an idea of how much the returns of a portfolio can fluctuate.

Portfolio: 4.89%

Benchmark (Liv-ex 100): 4.21%

Tracking Error: 1.48%

The tracking error measures the performance deviation from its benchmark. If you have a passive investment strategy that aims to mimic a benchmark, a low tracking error is desired. If you have an active strategy, a higher tracking error might be acceptable, but it indicates that the portfolio is deviating from the benchmark, which could be good or bad depending on the performance outcome. In our case, the portfolio is definitely not trying to mimic the benchmark and therefore considered an active strategy.

While both volatility and tracking error measure risk, they address different types of risk: total risk versus active risk, respectively.

Maximum Drawdown:

Maximum Drawdown is a crucial metric for understanding the downside risk and the potential losses an investor might face, as it measures the largest decline from a peak.

Portfolio: −7.00%

This means that, at its most significant decline, the portfolio dropped 7% from its prior peak value. Investors who entered the portfolio at its peak would have experienced a 7% decrease in the value of their investment before the portfolio started recovering.

Benchmark (Liv-ex 100): −10.75%

The benchmark experienced a more pronounced decline, with a maximum drawdown of 10.75%. This indicates that the Liv-ex 100, during its worst period, lost over 10% of its value from a prior peak.

The portfolio's active drawdown is 3.75% less than that of the Liv-ex 100 benchmark. This suggests that the portfolio was relatively more resilient during downturns when compared to the benchmark. A smaller drawdown for the portfolio implies that it might be better positioned to recover and achieve new highs, as it has less ground to make up after a decline.

Value at Risk

Value at Risk (VaR) is a risk management tool used in finance to quantify the potential loss in value of a portfolio or investment over a specified period and for a given confidence interval. In simpler terms, VaR gives investors an idea of how much they could lose in a worst-case (or near-worst-case) scenario.

Using the historical method, the 1-month Value at Risk (VaR) for the portfolio is as follows:

95% Confidence Level: Potential loss of 9.99% over a month. This means that there is a 5% chance that the portfolio will experience a loss greater than 9.99% over a single month.

99% Confidence Level: Potential loss of 10.45% over a month. This implies a 1% chance that the portfolio will experience a loss greater than 10.45% over a single month.

This provides a perspective on the downside risk of the portfolio in terms of potential single-month losses. It's essential to consider this alongside other risk metrics and the broader context of the portfolio's investment strategy and objectives.

Diversification

Diversification in a portfolio is the distribution of investments among various assets or asset classes to reduce risk. The main idea behind diversification is that a variety of investments will, on average, yield higher returns and pose a lower risk than any individual investment within the portfolio.

While normally fine wine should account for a small amount of one’s total wealth intended as an investment portfolio (<10%), in the context of this model portfolio I worked with two asset classes: cash and fine wine.

As a rule, I want to “invest” in cash when:

interest rates are rising and the risk-free interest rate is more than 1% above the inflation rate (the more above 1%, the more I want to invest in cash), and

when the real interest rate is at or above the economy’s real growth rate — or more simply, when the interest rate is above the economy's total growth rate (i.e., inflation plus real growth). The more above the inflation rate and growth rate, the more I want to invest in cash.

On that basis, that’s why I like cash now. If you have followed me during the past year, you would have noticed that I kept more than 50% of the portfolio in cash most of the time and currently have 20.5% in cash. The fine wine market nosedive has lots to do with this economic dynamic: investors are capturing a pretty good rate without the risk of losing principal, and if rates keep rising they will get more and more because they didn’t fix their rate.

Number of securities (wines): 16

Concentration Index: 0.11

The closer this value is to 1, the more concentrated (or less diversified) the portfolio is. The closer it is to 0, the less concentrated it is. Based on the concentration index alone, the portfolio appears to be well diversified. Of course, it’s a simplified metric that only accounts for the weight of each wine. If we dig deeper, we would notice that the portfolio is highly skewed towards Bordeaux and within Bordeaux, towards St-Émilion.

Why?

St-Émilion weighs heavily in the portfolio for two reasons:

Reclassification — I started this portfolio project just before the 2022 St-Émilion reclassification and I wanted to capture some of the positive returns that would have spurred from it if any of the châteaux had been upgraded.

It’s in vogue. Perhaps because of the noise made by the reclassification or because prices (and wines) are more accessible than their Pomerol or Left bank peers, it’s a region that has seen increasingly greater attention.

In addition, the portfolio reflects what I believe to be interestingly underpriced wines and regions. As I mentioned a few times (here and, more recently, here), I believe Barolo 2019 and 2013 to be fantastically undervalued vintages, perhaps because they have to live in the shadow of 2016.

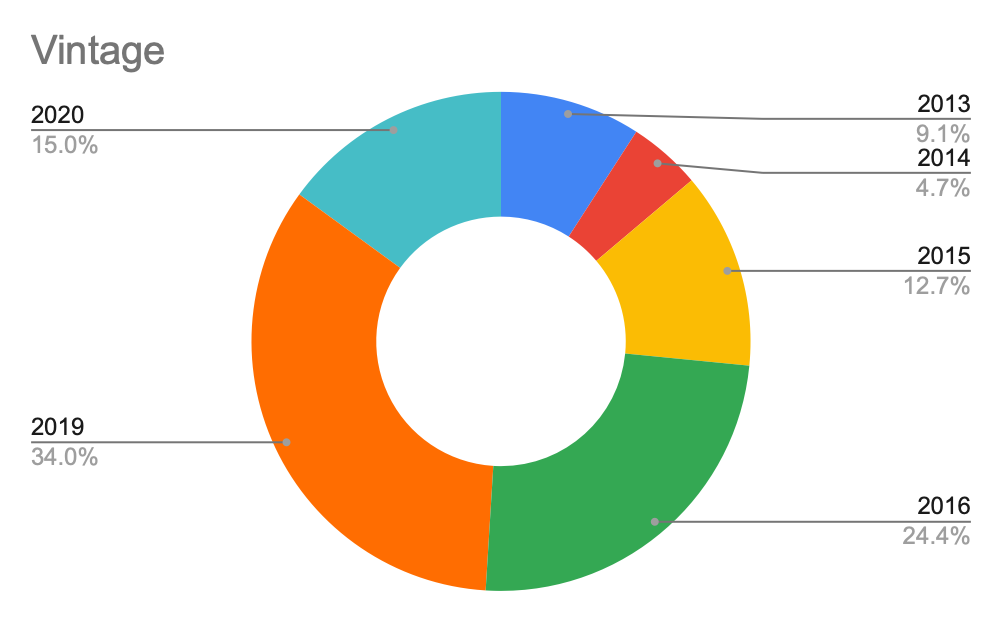

In terms of vintage selection, I am quite comfortable with the diversification and the breakdown. Over 60% of the portfolio is invested in ‘on-vintages’, which we know, will appreciate in value after bottling and rise strongly until maturity, while wines in ‘off-vintages’ have been purchased opportunistically.

Holdings

In absolute terms, the underperformance of this portfolio was driven by Ausone, while Figeac pared back some of the losses with its incredible rise to 1er Grand Cru Classe (1erGCC) A.

Holding 33% of the portfolio (for most of the year it had accounted for nearly 50% of it) in one single château is not the best diversification strategy. However, I hold the conviction that Ausone is one of the most undervalued châteaux in St-Émilion when looking at fair value and when compared to its peers — Cheval Blanc, Angélus, Figeac, Pavie.

One of the issues with fine wine investing is that one cannot buy smaller portions of wines and if you want exposure to a certain château with a high unit price, that’s the inherent risk that will weigh heavily on the diversification of the portfolio. I (incorrectly) held the conviction that, while outside the classification, the coverage of St-Emilion would benefit Ausone. It didn’t.

I have added both Canon and Figeac to the portfolio ahead of the St-Émilion reclassification, thinking that they both had a chance to move up. Figeac contributed very positively to the portfolio — and for this reason, I sold half of my allocation to lock in some positive returns. This strategy added 3% overall to the yearly performance.

I believe that Barolo 2019 and 2013 are undervalued vintages in the region. That’s why I added a few names from the Ravera cru. I could have added more — and I’ll probably will in the next few months. Stay tuned!

All the other names didn’t have a region-wide theme behind them, I just believed them to be undervalued wines and added them opportunistically.

Final thoughts

When operating in a market with higher transaction costs, a more strategic, long-term approach to investing is necessary. Reacting to short-term market fluctuations can be detrimental, not just because of market unpredictability but also due to the increased costs associated with frequent trading.

Thanks for tuning in this week! This newsletter is free for all readers and the best way to keep it free is to subscribe, re-share it with your wine-lover friends, and follow me on Instagram.

👋 Sara Danese

Comments, questions, tips? Send me a note

In case you missed it:

Subscribe to In the mood for wine …

Disclaimer

My investment thesis, risk appetite, and time frames are strictly my own and are significantly different from that of my readership. As such, the investments covered in this publication and in this article are not to be considered investment advice nor do they represent an offer to buy or sell securities or services, and should be regarded as information only.