Is Wine Going Out Of Fashion?

Analysing the long-term case for investing in wine

When, on 4 January 2023, the World Health Organisation published a release titled “No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health”, I wasn’t particularly surprised.

That’s because, five months earlier, Andrew Huberman—Stanford professor of neurobiology and ophthalmology and host of a hugely popular podcast— published a two-hour episode titled “What Alcohol Does to Your Body, Brain & Health,” in which he lists the problems associated with alcohol—yes, even with moderate consumption. Since then, the video has racked up 7.4 million views—not to mention all the podcast listens and high-profile interviews Huberman has done since (for example this, with Chris Williamson), where he states in no uncertain terms that drinking even one drink per week is bad for you.

More recently, “alcohol is a leading preventable cause of cancer, and alcoholic beverages should carry a warning label as packs of cigarettes do,” the U.S. surgeon general Dr. Vivek Murthy said.

Self-explanatory in their (unified) messages, they focus on the harm caused by alcohol—even in moderate doses.

Not the beverage, though, that’s what the WHO wrote in one of these bold headings.

If it was a way to tame concern in the wine industry, it didn’t work.

Concern in the wine industry spread like wildfire.

Many publications responded to the WHO’s release, but the most compelling critique came from Felicity Carter in her piece, “How Neo-Prohibitionists Came to Shape Alcohol Policy.” Carter argues that the WHO’s approach is heavily influenced by temperance groups, oversimplifies the science, ignores cultural nuance, and risks sidelining more moderate, evidence-based strategies. Another strong rebuttal comes from Konstantin Baum MW, whose video “The TRUTH About ALCOHOL and why Andrew Huberman is wrong” presents a balanced counterpoint to the black-and-white thinking that so often defines our times.

As you can probably imagine, I’m very sympathetic to these arguments—and to the idea of moderation in wine (and in life!) But I also think it’s important to acknowledge that I (and likely many of you reading this) am rooting for wine.

And, amid such partisan debate, it can be difficult to separate fact from rhetoric. Regardless of how we feel about drinking wine, we can’t ignore the growing negative sentiment surrounding it.

So it’s fair to ask: how bad—or how good—could things get for wine?

It is hard to pin down the future of wine with any degree of certainty, and even when pinned down, rightly or wrongly, it tells us little about the consequences.

Take the tobacco industry.

While it’s now almost impossible to see anyone smoking, if you’d put your hard-won pennies into BAT, Imperial Brands, or any of the other major players, you’d have earned an annual dividend of around 5–7%—including during the pandemic, when most other high-dividend stocks cut or suspended their payouts entirely. On top of that, you’d have seen solid average yearly capital gains.

As analysts at BlackBull Research pointed out: “I know investing in tobacco isn’t exactly fashionable anymore, but the truth is: tobacco generates tremendous profits. BAT’s net income margin sits at 39.1%—few businesses come close to such operating margins. (Visa? What other company?)”

While you might think the anti-tobacco lobbies have won, tobacco companies are doing just fine.

Which brings me back to my original point: even if we think we know what the future holds for wine, we still have no idea what the consequences will be.

Since that January day of two years ago, many parallels have been drawn between wine and the tobacco industry. But as I explained above, my biggest worry isn’t that wine will become the new tobacco—it’s that it could become the new fur.

Like wine, fur was once a marker of status.

Unlike cigarettes, its downfall wasn’t triggered by hard science or public health policy. It was driven by a generational shift in values—a slow cultural pivot that made something once aspirational suddenly feel outdated, unethical, and embarrassing.

The fashion industry was very late to catch on. Even now, Vogue’s editor-in-chief Anna Wintour still insists that alternatives to fur aren’t viable. But the consumer has already moved on. Morality changed the conversation.

Fur wasn’t banned—it was cancelled.

Crucially, both industries share deep roots in craftsmanship and artisanality. Their value was historically derived from rarity, skill, and terroir—the belief that no two coats (or wines) are quite the same.

That’s a world away from tobacco, which industrialised early and proudly. It was built on scale, addiction, and marketing, not nuance or origin.

Still, the absence of a “Big Wine” equivalent to “Big Tobacco” doesn’t mean wine is safe from attacks. If anything, the threat is greater. With innovation and lobbying fragmented across thousands of small producers, the industry lacks the unified force—and cash reserves—needed to fight back.

In a similar fashion, the bigger threat for the wine industry may not come from the WHO and the anti-alcohol lobbies but rather from a growing health trend driven by influencers and health-conscious TikTokers and YouTubers who advocate for minimal or no alcohol consumption.

In his extraordinary piece “The Anti-Social Century” for The Atlantic, Derek Thompson discusses philosopher Andrew Taggart, who refers to that certain kind of modern individual as a “secular monk”—people who combine old-fashioned austerity with a new kind of solipsism. (Think: Andrew Huberman, Ashton Hall, Chris Williamson,…)

“Instead of focusing their 30s and 40s on wedding bands and diapers, they were committed to working on their body, their bank account, and their meditation- sharpened minds […] by submitting themselves to ever more rigorous, monitored forms of ascetic self-control, among them, cold showers, intermittent fasting, data-driven health optimization, and meditation boot camps.”

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

We’ve all seen the viral morning routines of these people. But as Thompson points out, what’s most striking about these videos is not what they include—but what they leave out: other people.

“In these cinematic portraits of the “life well lived,” the protagonists usually wake up alone—and stay that way. There are no friends, no spouse, no children. These videos are, in effect, advertisements for a luxurious form of modern monasticism—one that sees the presence of others as, at best, an unwelcome distraction and, at worst, an unhealthy indulgence to be avoided entirely.”

It’s this broader trend—of the anti-social century and its simplified, moralising messages like “alcohol is bad for you”—that could ultimately serve as the catalyst for wine’s debacle.

I asked Carter point blank—Will this affect the wine industry?

She simply replied “Yes.”

“But fine wine however,” she added “won’t be affected as much, a bit like cigars.”

Cigars?!!

I hadn’t even realised people still smoked them!

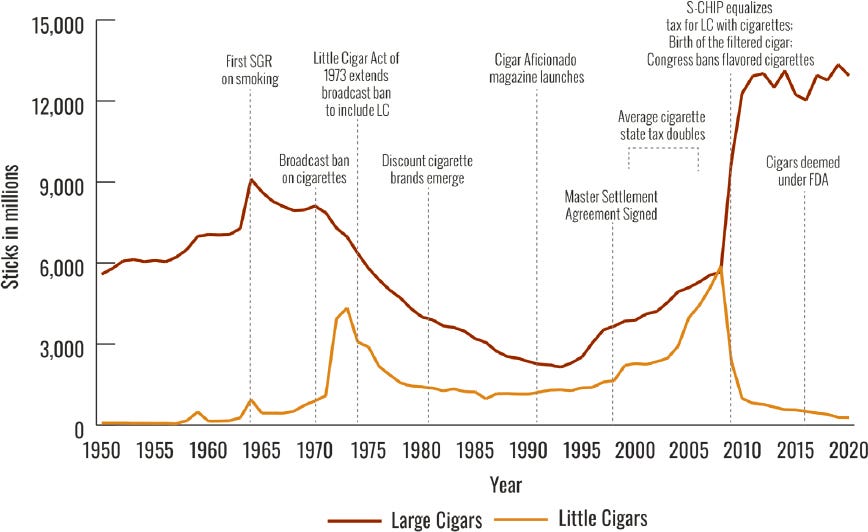

Surprisingly, not only do people still smoke cigars—but they’ve actually benefited from the anti-smoking movement. Between 2009 and 2020, cigar sales rose from $2.47 billion to $3.27 billion.

As cigarettes became socially and culturally unacceptable, cigars were repositioned as luxury items. Their image was reinforced through lifestyle magazines, celebrity endorsements, product placement in films, and associations with upscale fashion, cars, and jewellery.

Cigars didn’t just survive—they found refuge in status.

As anti-alcohol sentiment intensifies, mass-market wine consumed for its intoxicating effect is under threat. Fine wine, however, could occupy a different category. It can reposition itself not as a drink, but as a luxury good—decoupled from problematic drinking behaviours and associated instead with craft, culture, and scarcity.

In this context, fine wine is more likely to survive—not because it’s exempt from scrutiny, but because it’s consumed differently: in private settings, curated tastings, and premium dining experiences. It is valued for its artisanal production, unique characteristics, and long-term appreciation.

This shift could also reshape demand. Casual drinkers may vanish, replaced by a more discerning customer—someone who views wine as an object of craftsmanship, and investment, rather than for just consumption.

And that’s where the opportunity may lie: in crafting a more inclusive definition of fine wine. But that’s a topic for another time!!!

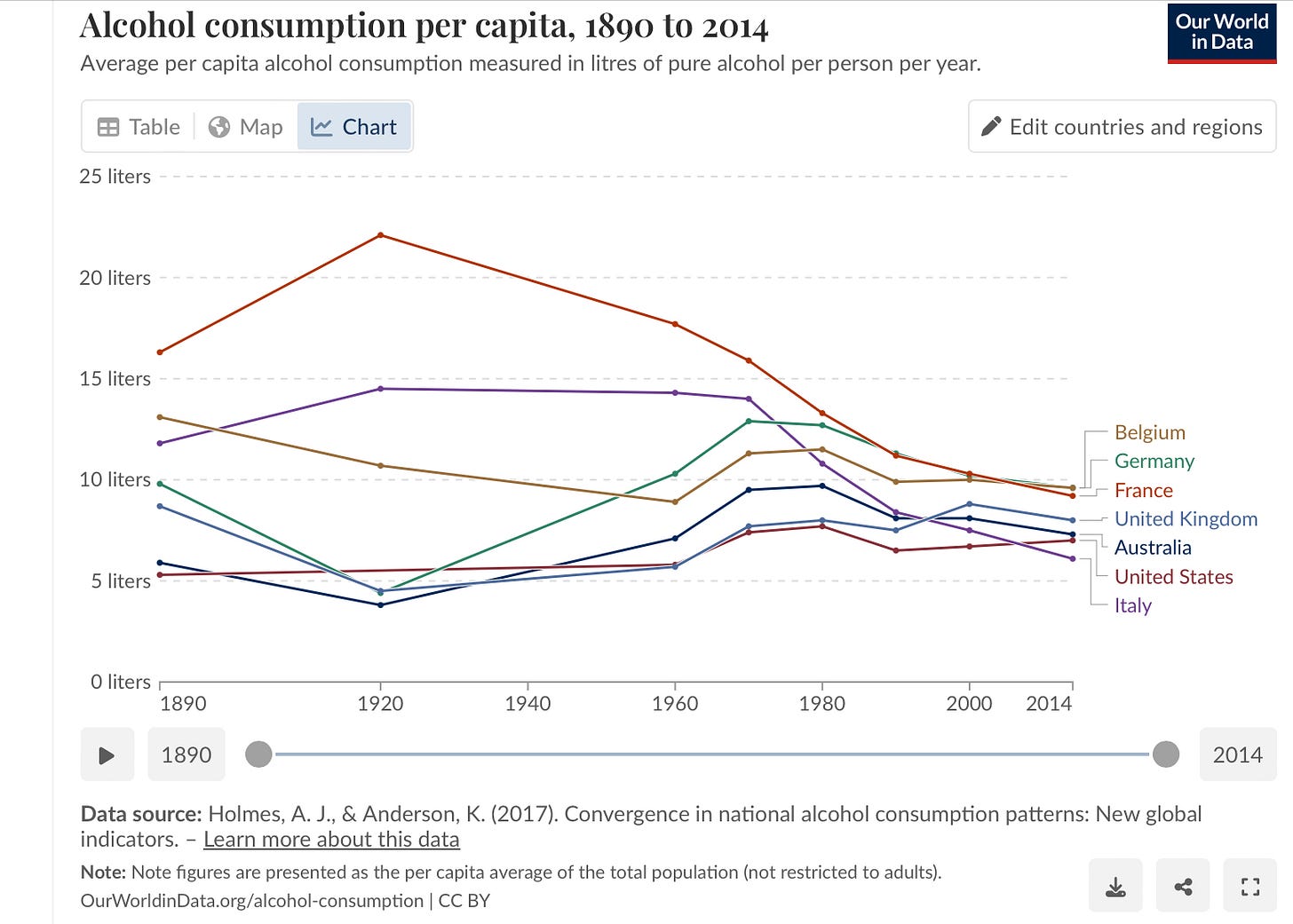

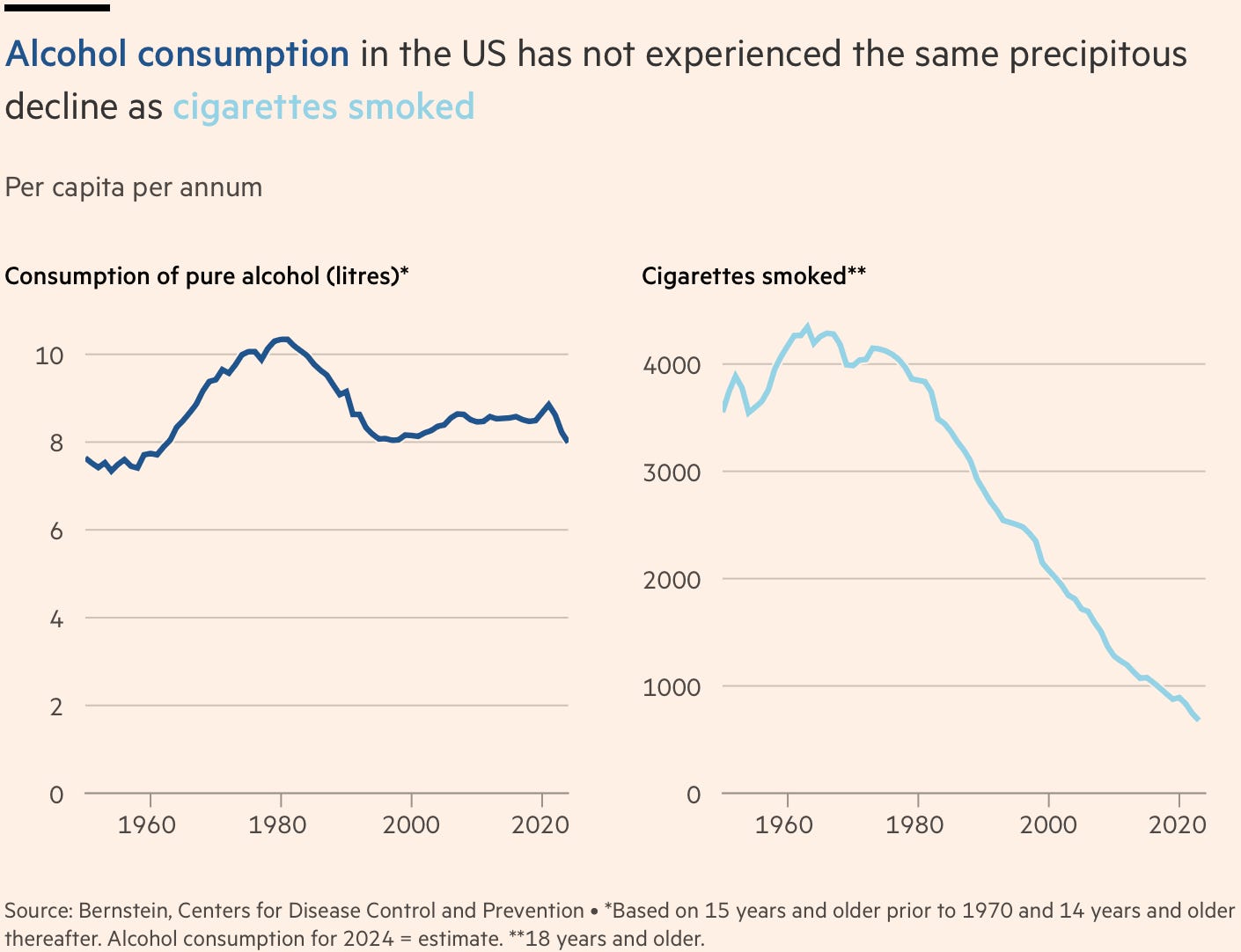

More than any other economic indicator, the decline in alcohol consumption is the focus of the industry, particularly as many wonder if wine will suffer the same fate as tobacco. Consumption has been falling for a while and, as the FT pointed out, is now at its lowest since 1962. Young people aren’t drinking as much. That’s triggering industry-wide panic.

But there are some important caveats.

While alcohol consumption is declining, it’s instructive to look at the historical context.

Alcohol consumption has largely normalised over the past few decades. While per capita consumption may have declined, overall alcohol sales have returned to pre-pandemic levels.

How is it possible?

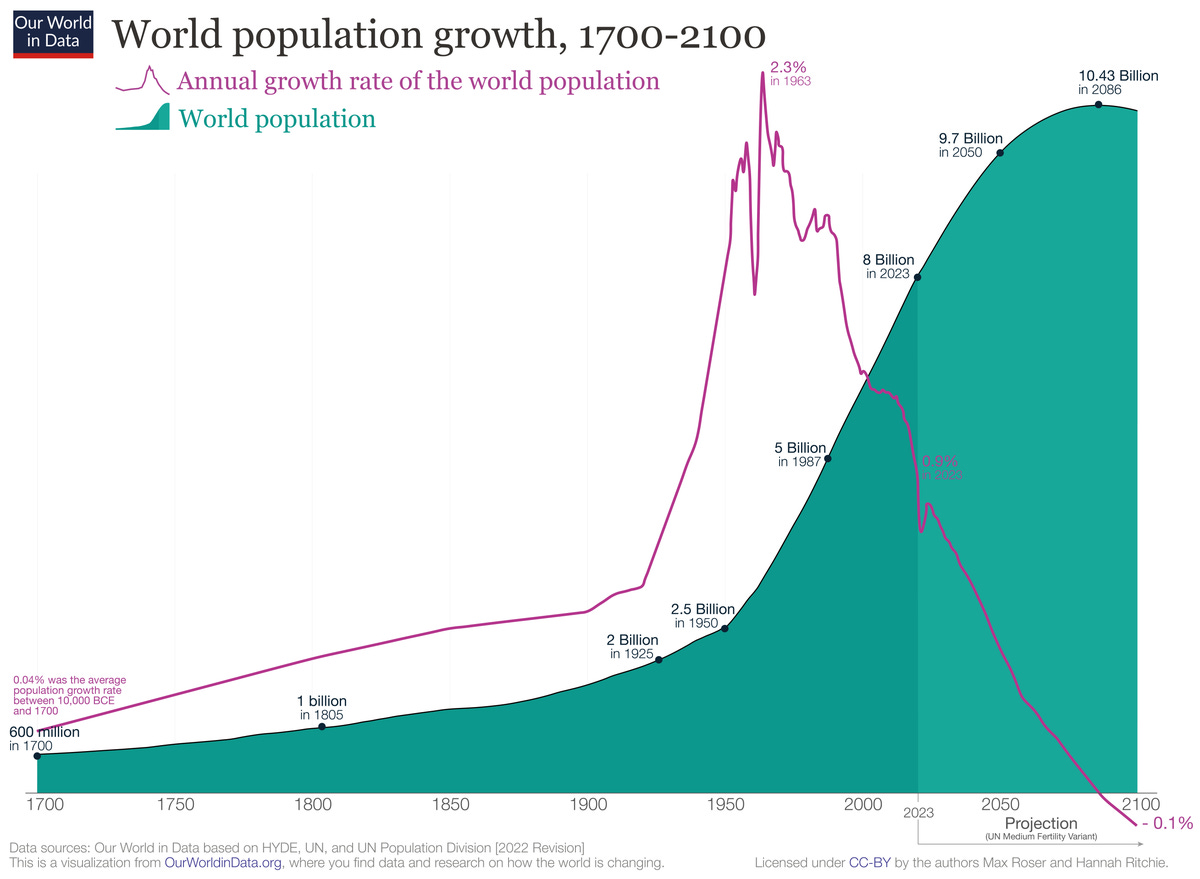

For the same reason sales of cars or other consumer goods keep rising—global population growth—around 1% per year.

What’s more, as Simon Farr, Chairman of Cru World Wine, points out, the universe of buyers continues to expand. “As global wealth increases, more consumers in emerging markets are developing a taste for the finer things in life, often inspired by consumption patterns in more developed economies.”

In addition, the decline has been gradual—not a sudden collapse like tobacco in the 1990s.

In either scenario—whether wine follows the path of fur or cigars—moderation will lead. Debra Crew, CEO of Diageo, recently described moderation as the industry’s “biggest disrupter,” according to the Financial Times.

Laurence Whyatt, Head of European Beverages Research at Barclays, also cautions against overinterpreting the data on declining youth consumption. Much of it, he notes, comes from surveys and is therefore not entirely reliable. Barclays’ own research found that Gen Z is spending a similar—or even higher—proportion of their income on alcohol compared to previous generations.

Another major concern is what Derek Thompson refers to as “solitude”—the growing amount of time people spend alone, and crucially, how comfortable they’ve become with it.

Vivek Murthy, the same surgeon general of the U.S. that warned us that “alcohol is a leading preventable cause of cancer”, published an 81-page warning about America’s “epidemic of loneliness,” claiming that its negative health effects were on par with those of tobacco use and obesity.

“A growing number of public-health officials seem to regard loneliness as the developed world’s next critical public-health issue,” writes Thompson. “The United Kingdom now has a minister for loneliness. So does Japan.”

I am not here trying to suggest that the lack of one (alcohol) causes the other (loneliness)—far from it!

What I do believe is this: while we may appreciate the flavour and complexity of wine, its endurance over centuries is rooted in its role as a social lubricant. The two are inseparable. You can’t address one without acknowledging the other.

People use wine—and have for centuries—because it makes social interactions a little less awkward and a little more fluid. It smooths the edges of conversation, especially in situations where connection doesn’t come easily.

If you’ve ever been the only sober person in a group, you’ll know—it’s not much fun. During my pregnancy, it felt as though my hormones had the same effect as Ozempic: they completely killed my desire for a drink. It wasn’t meeting close friends that became harder. It was the encounters where connection required a bit of help—those more uncertain social spaces—that truly highlighted wine’s role as a social lubricant.

In countries where alcohol is restricted or unfashionable, social gatherings typically centre around food. This isn’t limited to Muslim-majority nations—it’s also true in places like China, where alcohol may play a role but is rarely the main event.

But if we accept that trends like Ozempic signal the decline of alcohol consumption—and possibly a waning interest in food—then we’re not just looking at the death of drinking. We’re looking at the slow erosion of the traditional social gathering itself.

Because if meetings are no longer centred around food or drink, the question becomes: what will they be centred around?

Felicity Carter notes that the anti-tobacco movement succeeded by de-normalising smoking, particularly by banning it in places frequented by children—restaurants, public spaces, indoor venues. If a similar approach were applied to wine, the impact on the hospitality sector will be profound.

The global hospitality industry is a substantial economic force, with revenues reaching $4.9 trillion in 2024, accounting for approximately 10% of global GDP. This sector encompasses a wide range of services, including hotels, restaurants, bars, and event planning, all of which often involve alcohol as a central component of their offerings (and their margins!)

Implementing widespread restrictions on alcohol consumption in public venues could therefore have significant economic repercussions, potentially affecting employment, tourism, and related industries.

While it’s possible to envision a future where alcohol plays a diminished role in social settings, such a shift would necessitate a comprehensive reevaluation of social norms and economic structures.

In this context, concerns about the future of wine are just one part of a much broader societal transformation—and that’s precisely why I believe the de-normalisation strategy that proved so effective for tobacco will be far more difficult to apply to wine.

In the long term, I see wine consumption to follow a path similar to that of meat. Just as some have embraced veganism while others have simply reduced their intake and chosen to enjoy less but better-quality meat, wine drinkers may do the same. Some will abstain entirely, but many will gravitate toward moderation and premium wines.

As with meat, I believe the real loser in this transition is likely to be low-quality, mass-produced wine.

For investors, this moment calls for both caution and clarity. The market is evolving—but that doesn’t mean wine is becoming obsolete.

The simultaneous rise of low- and no-alcohol alternatives and sustained demand for fine wine suggests a future where quality and choice, not volume, define the category.

To echo Debra Crew once more: moderation will be the greatest challenge facing the future of this industry.

I believe the future of wine will be shaped by exceptional vineyard sites, cutting-edge viticulture, experimentation with both heritage and emerging grape varieties, and a new generation of highly educated winemakers. We'll see a focus on terroir—both new and old—parcel-based production, smaller-scale operations, and advanced techniques. Add to that modern packaging and infrastructure that better suits how wine is made, tracked, sold, and delivered, and you begin to get a sense of the transformation underway.

In this world, wine will likely become more expensive, but I don’t believe the overall cost of drinking wine will necessarily increase. A shift toward quality over quantity, combined with an evolving consumer base, means that fine wine is well positioned to weather these changes.

At the same time, the pool of potential buyers is expanding. As Simon Farr has noted, rising global wealth is fuelling demand for fine wine, with newly affluent consumers increasingly emulating the tastes of more established markets.

Yet production remains relatively static, creating a persistent imbalance between supply and demand. In the short term, that imbalance is resolved through higher prices—until a new equilibrium is reached.

But!!!

I don’t want to end this investment piece on an entirely optimistic note.

The wine industry is facing two significant risks:

The Storage Pricing Issue

When wines are released at prices that ignore storage costs, opportunity cost, or market reality, they lose their appeal—not just to drinkers, but to merchants as well. Overpricing at release, especially when paired with the trend toward producing more approachable styles (as I discussed in my piece for Tim Atkin— The Truth about Myths), reduces the volume of fine wine entering long-term cellars. In my view, this not only weakens the long-term investment case but also undermines wine’s intrinsic value.

Turning Away the Next Generation

There is a serious risk of alienating younger consumers, and it’s happening in multiple ways. As fellow Substackers from BlackBull Research recently wrote:

“There’s still cause for worry — I think wine is one area of concern, and Cognac is another — both industries need to think about how they introduce younger drinkers to their product.”

I’d go further.

The wine industry is failing to create the infrastructure younger consumers expect:

No seamless backend for buying, storing, or delivering wine.

Pricing models (especially for en primeur) that feel arbitrary or nonsensical.

Sales and communication styles that don't match younger buying habits.

So, the threat to wine doesn't come from exogenous factors—not even from Gen Z drinking less. It comes from the industry’s own inertia.

The story, however, isn’t entirely bleak.

We can learn from tobacco’s example. Despite heavy regulation and cultural backlash, tobacco companies adapted: they launched new product formats (vapes, e-cigarettes) and expanded into new markets across Africa and Asia, continuing to thrive.

The wine industry is already showing similar signs of adaptation—notably in the rise of low- and no-alcohol products. These aren’t just cannibalising existing wine drinkers, they’re in fact expanding the audience. People who previously had no place at the table—due to health, religion, or preference—are now being offered something adult, sophisticated, and inclusive.

Once again, the future of wine won’t be determined by external forces alone—but by how the industry chooses to respond.

Thank you for reading.

Sara

…and, for those of you who stayed till the end, a little question:

Resources

Felicity Carter’s Substack Drinks Insider

How Neo-Prohibitionists Came to Shape Alcohol Policy (Felicity Carter, WineBusiness Monthly)

The TRUTH About ALCOHOL and why Andrew Huberman is wrong (Kostantin Baum, Youtube)

Temperance Nutt (Christopher Snowdon, The Snowdon Substack)

‘No good evidence’ of risk from low-level alcohol consumption (The Drinks Business)

NASEM report affirms benefits of moderate drinking (Felicity Carter, WineBusiness Monthly)

But, is alcohol the new tobacco? (BlackBull Research)